Canadian advocates for universal health coverage in the 1960s underpinned their fight with rights-based arguments. Former Saskatchewan premier Tommy Douglas, voted the greatest Canadian in a 2004 CBC poll, insisted that health care should be a basic and universal right of citizenship, and that no one should be denied care because of an inability to pay. Today, these positions are largely non-negotiable across the Canadian political spectrum.

Canada’s commitment to universal health coverage as a human right should extend into our international assistance policy and advocacy efforts. On Sept. 23, the international movement for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as a fulfillment of fundamental human rights will gain unprecedented visibility at the first United Nations High Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage. Canada’s vocal participation in the emerging global UHC dialogue is both an obligation and an opportunity.

Activists rightly lauded Canada’s ongoing commitment to the rights and health of women and girls following the government’s 10-year funding pledge this summer in support of health, empowerment and gender equity initiatives globally. Within the context of Canada’s feminist international assistance policy, the push for UHC remains an issue deserving of greater visibility. The rights of women, girls and children – and the impact of Canada’s investments – will be strengthened when UHC is the shared goal of individual countries and the international donor community.

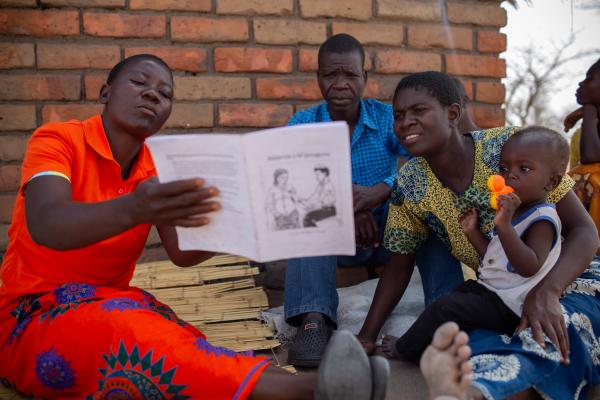

One of UHC’s key aims is to achieve equity in access to quality health services – which means that everyone can get the services they need (without financial hardship), and that those services are of high enough quality to improve health. For the public health system of a poor country, this requires allocating resources in ways that address the disproportionate health burdens of the most vulnerable members of the population, particularly women and girls. (Such burdens include high maternal mortality, TB and HIV, malnutrition, but also increasingly diabetes, heart disease and other non-communicable diseases). It demands strengthening health systems by improving facilities, staffing, supply chains, and bringing care closer to communities through the use of community health workers – all of which also build public confidence in and increase use of public sector health services.

The benefits of such an approach for a country’s development are seen in countries such as Rwanda and Lesotho. Over the past 15 years, Rwanda has achieved unprecedented reductions in morbidity and mortality by focusing resources on strengthening the national primary care platform, improving cross-departmental coordination, and requiring that all international aid aligns with national priorities. Lesotho, currently in the fifth year of a national health reform, aligned and decentralized resources to meet specific UHC targets and invested in both health management leadership and community engagement. Facility-based deliveries have doubled, immunization rates dramatically increased, and testing for HIV and cure rates for TB have skyrocketed.

At the UN meeting, developing country governments will be encouraged to allocate a greater share of national budgets to health spending. Among the key recommendations by UHC2030 – an international coalition of civil society, private sector, academia and government partners, including Canada – is for the international community also to invest more and invest smarter. Canadians should see this as an obligation. For centuries, massive extraction of financial and human resources by the global north has had devastating impacts on the communities our organizations partner with in Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. Historical forces have shaped global disparities and undermined public sector capacity in resource-poor settings, and this must inform our response now to the UHC demand.

It is also in our self-interest to do more. Time and again (most recently with the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and the current outbreak in DRC), it has cost the international community far more to fund emergency outbreak containment measures than to give long-term support for public health systems that would treat populations and prevent disease spread.

As women bear a disproportionately large share of the global burden of disease and death, Canada should ensure that the political declaration on the global UHC agenda to be signed by world leaders on Sept. 23 puts women’s and girls’ health and rights front and centre. Advancing UHC as a development objective will make our aid dollars achieve more, and will bring about better quality care for women, adolescents, and children.

It’s also an expression of Canadian values: if we see health as a human right for our own citizens, the push for universal health coverage can’t stop at our country’s borders.