Haiti is still grappling with a pernicious cholera epidemic nearly five years after the disease’s first appearance in the country. Cases spiked from 1,000 per month last summer to 1,000 per week in the fall, according to Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health and Population. There were nearly 8,400 cases in January and February alone and 82 deaths—twice as many cases and three and a half times as many deaths over the same period last year.

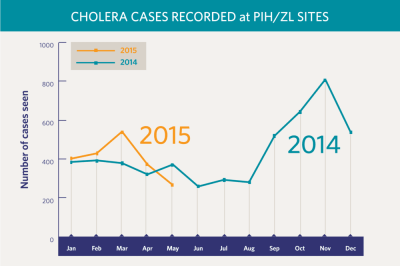

Beyond Port-au-Prince and its suburbs, the Artibonite and Centre regions—the hub of operations for Zanmi Lasante (ZL), Partners In Health’s (PIH) sister organization in Haiti—have been among the hardest hit, especially the communities of St. Marc, Mirebalais, Hinche, and Lascahobas. There were 5,179 cases across all PIH/ZL sites in 2014. The worst spike was over the last four months of the year, peaking at 808 cases in November alone. That monthly tally slowly declined and then bumped back up to 540 cases in March this year. So far, PIH/ZL staff are seeing two or three times as many patients in 2015 as they did over the same period last year.

This wave of cases is like a recurring nightmare for Dr. Ralph Ternier. A big part of his job as ZL’s director of community care and support is to prevent the disease’s spread, which can be as simple a task as reminding patients to wash their hands with soap and water. But patient follow-through is the tricky part. They often ask him, “Where am I going to find soap and water?”

That’s the reality for many Haitians. About 40 percent lack access to clean water, and only one in four have access to a sanitary toilet, according to the World Bank. Even if they do have safe water and proper sanitation, “many Haitians are so poor that they’re literally choosing between buying soap one day or buying food for their family or for their children,” Dr. Louise Ivers, PIH’s senior health and policy advisor, told NPR in a recent interview. The World Bank reports that more than half of Haitians live under the national poverty line of less than $2.50 per day.

Cholera spreads when people come in contact with contaminated sewage, usually through consuming unclean food or water. This happens with relative ease in communities without proper latrines, and where torrential downpours during Haiti’s rainy seasons in the spring and fall cause daily flash floods. People who contract cholera suffer excessive vomiting and diarrhea and can die of severe dehydration within 24 hours.

Haiti never knew cholera until 2010. That’s when the United Nations flew in a group of peacekeepers from Nepal, whose capital had recently suffered an outbreak of the disease, and set them up in a camp with poor plumbing. Contaminated sewage leaked into a tributary of the longest river in the country, the 200-mile Artibonite. Since the first person was diagnosed in October 2010, there have been more than 739,000 cases of cholera and 8,900 deaths, according to Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health and Population.

So why does cholera continue to plague Haiti, and PIH/ZL sites, five years after the initial outbreak?

“We haven’t gotten rid of the reasons for the transmission of the bacteria, and that’s because there’s such poor water and sanitation,” Ivers says. Since the outbreak began, “there have been no transformative water and sanitation activities, and so the underlying problem is still there. I think that’s why the number of cases has started to go up again.”

Ivers also says numbers may be higher where PIH/ZL operates because the Centre region is one of the poorest in the country and, therefore, has limited water and sanitation infrastructure. Plus, staff actively record cholera cases, something that is not true everywhere in the country because human resources are lacking. A full count of the disease could be much higher nationwide.

In response to the epidemic, the governments of Haiti and the Dominican Republic proposed a 10-year, $2.2 billion plan to eliminate cholera, including investments in new water and sanitation systems. But that plan, announced in 2012 and supported by an international community of donors, is only 13 percent funded.

Some advocates believe the U.N. should shoulder more of the burden for cholera in Haiti. Brian Concannon and the non-profit he co-founded, the Institute of Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), has requested the U.N. accept responsibility for the initial outbreak. (For more on the international body’s role in the epidemic, see Ivers’s op-ed in The New York Times.) The IJDH filed a lawsuit against the U.N. in U.S. federal court in 2013, but a judge dismissed the case in January 2015. The organization is now appealing that ruling.

Meanwhile, Ternier and his staff do what they can to halt the most recent spike in cases, as they’ve done with others in the past. They mobilize a network of community health workers to find patients, open rehydration posts in remote locations, educate people about proper hygiene and sanitation, and diligently work to bring reliable water and sanitation systems to the region.

More comprehensive work needs to be done. In a 2010 article published in The Lancet (“Five complementary interventions to slow cholera: Haiti”), Ivers and Dr. Paul Farmer, a PIH co-founder and chief strategist, laid out a detailed roadmap to break the cycle of cholera. They wrote that health care professionals have to aggressively find and treat cholera cases and administer vaccines such as Shanchol, which Ivers and her colleagues found reduced the number of cholera cases by 63 percent among those vaccinated in villages north of St. Marc. Water and sanitation systems need to be improved. Public health care systems have to be strengthened. And global health policy must be crafted to give cholera the level of attention it deserves.

All this takes time, something that isn’t always on the side of Ternier’s patients. Regardless, he keeps treating them for cholera and reminding everyone of the message he’s repeated for years. He knows “this is not something that we’re going to solve in five years.”

But it is something PIH/ZL knows how to tackle, and will, for as long as it takes.