All over the world, millions of girls are denied basic human rights, such as access to health care and education. Since 2012, October 11 has marked the annual International Day of the Girl, a celebration that advocates for girls’ empowerment and human rights.

This year, at Partners In Health, we are celebrating girls who have broken down barriers, defied stereotypes, and beaten the odds to work toward their dreams.

Promoting gender equity is a central mission at the University of Global Health Equity (UGHE), a PIH initiative in the rural, northern Rwanda community of Butaro. When admitting its first class of medical students, the university prioritized the education of young women, who have been historically underrepresented in higher education and medicine in Rwanda.

The inaugural class includes 30 students, two-thirds of them women. Every one of them has a strong belief in health equity and providing for the poor. Today, we share the stories of three of these young women, each of whom had experiences as young girls that have inspired them to pursue careers in global health.

For this International Day of the Girl, we celebrate their achievements, and their journeys toward becoming the next generation of women leaders in global health.

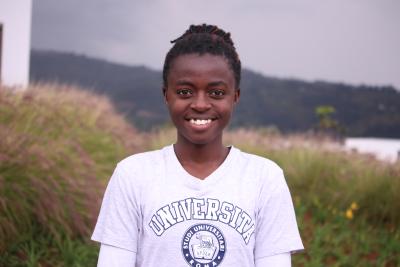

Alima Uwimana

Danny Kamanzi / University of Global Health Equity

Alima Uwimana

‘We are still so grateful’

Alima Uwimana, 20, could hardly believe where she was when she stepped foot on campus in Butaro, alongside 29 strangers who would be her classmates and community for the next six and a half years. For her entire life, until that moment, her new reality had never seemed like a possibility.

Uwimana grew up in a rural village in western Rwanda, near borders with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. Her family often struggled with money, and never thought they’d be able to send her to university.

But Uwimana, the youngest of 10 children, now could be the first to graduate from college. Of her six sisters, she is the only one to make it to high school, where she excelled in the sciences and worked hard to maintain good marks.

She now is attending UGHE on a full scholarship, thanks to the generosity of UGHE donors and a partnership with Rwanda’s Ministry of Health.

“We were all laughing and smiling so much,” Uwimana said, recalling the moment she and her family learned she would join UGHE’s inaugural medical class. “We were so thankful. My family had no idea it was possible for me to get a full scholarship. We are still so grateful.”

Uwimana is an aunt, with 28 nieces and nephews, and she wants to help each of them believe in themselves and pursue their passions, as she did.

“I want to show them that even though they may not have a lot of money, if they have commitment and patience and if they study hard, they can achieve their dreams,” she said.

Uwimana knew her dream at a young age. She remembers watching television as a girl and listening to Rwanda’s newest minister of health at the time, Dr. Agnes Binagwaho—now UGHE’s vice chancellor—outline her vision for the country’s health system. Binagwaho called for quality health care for all and an agenda that focused on the poor and vulnerable.

Uwimana thought about her own family, who had faced so many challenges with the health system due to financial difficulties, and how Binagwaho’s vision could affect them.

One of Uwimana’s brothers lost his abilities to speak and hear, due to ailments that could have been cured had their family had the money for the specialist he needed. Her nieces and nephews, the very ones she hopes to inspire with her career, have often suffered from malnutrition, and her siblings have gone into debt to get them treatment.

Listening to Binagwaho, Uwimana began to understand not only her feelings while watching her family’s struggles, but also how she could help. She could become a doctor who cared for those in need, regardless of their economic status. She thought that maybe she could even be Rwanda’s minister of health and, like Binagwaho, change the system so families like hers could get the health services they needed.

“I was inspired by the way she put the health of the citizens first, and she is the one who first saw that everyone deserves health regardless of financial capacity,” Uwimana said. “I was inspired by her and thought, one day, maybe I could be like her.”

Now, as a first-year medical student at the university led by Binagwaho, Uwimana can’t help but smile when asked how she feels about studying under the woman who inspired her, years ago, to pursue this path.

“I’m so happy and excited. I feel blessed being here,” she said, glancing toward the entrance to Binagwaho’s office. “I feel that I will achieve my dream of being a medical doctor who will be serving the vulnerable and the poor who are in need.”

Marie Immaculee Dusingize

Danny Kamanzi / University of Global Health Equity

Marie Immaculee Dusingize

‘A smile is enough’

Marie Immaculee Dusingize, a 19-year-old from Rwanda’s Southern Province, knows the inside of a hospital far too well for someone her age.

When she was 10, she started complaining of debilitating stomachaches. She couldn’t keep food down and had to resort to an extremely strict diet to minimize her pain. Dusingize spent many days and nights in different hospitals and health centers seeking treatment, but to no avail. To this day, she still experiences aches and pains and maintains the same rigid diet.

Her time in the hospital, while challenging, opened Dusingize’s eyes to the problems people face seeking health treatment. Her experiences left her dissatisfied with the quality of available health care, but it was the inequities she saw in the experiences of other patients that truly had an impact on her.

“I remember someone rich came in with just the flu and got treated right away, while someone with a serious kidney condition had no money for the exam and was turned away,” she said . “How can poor people die in front of the door of the hospital just because they don’t have money to pay?”

Dusingize has always looked out for others in need. Early in high school, she noticed how many graduating students would throw away most of their things at the end of the year. She thought about her neighbours—who couldn’t afford basic needs like shoes, clothing, and school supplies—and realized she could do something. So she stood next to the trash can, and when students came to throw their things away, she would ask them to give them to her instead.

“My friend saw me by the trash can and asked what I was doing, and when I explained it to her, she helped me announce it to the school. We decided to make it permanent,” she said. And that was the origin of her nonprofit, Charity Foundation. “Every time we throw away things we no longer need, those things may be useful to those who can’t afford them.”

Dusingize attributes this selflessness to her mother, who showed her the power of a helping hand. Her mother has been by her side throughout her years of illness. While her mother has no formal medical training, Dusingize says she has been a healer in her own way.

“What I learned from her is that we should give what we have. It’s not necessary that we say that, because I am not a medical doctor, I can’t help,” Dusingize said. “A smile is enough. She could always smile at me and say words that would make me forget that I was even sick, so I really regard her as a medical doctor.”

The values that Dusingize draws from her mother have guided her to where she is today.

“When I become a doctor, it will be my chance to give out what I have never been given or what I have seen others deprived of,” she said. “I feel like the world will be mine to change.”

Eden Gatesi

Danny Kamanzi / University of Global Health Equity

Eden Gatesi

‘We share the same vision’

Eden Gatesi didn’t get to spend much time with her mother when she was growing up. Her mother was a nurse, and would leave early in the morning to take care of patients, then return home late at night. The precious time they spent together, however, had a big impact on Gatesi.

“What impressed me most was even the little time she could spend at home, we would get visitors coming over to thank her for saving the lives of their beloved ones,” Gatesi recalled. ”That showed me that dedicating my life to being a health professional would help me to have an impact on my community and save their lives as my mom does.”

Although Gatesi knew she wanted to follow her mother’s footsteps, she felt pressured by societal and cultural norms. Many people in her life didn’t understand how she could spend so many years at school, and felt she should instead focus on raising a family. She didn’t know a single female cardiologist, the profession she knew she wanted to pursue. Gatesi, herself, began to experience doubts about whether she should follow her dreams.

All that changed in 2016, when Gatesi was invited to attend a prestigious camp called Women in Science, organized by the UN-backed nonprofit GirlUp. The camp was an opportunity for girls from across the globe interested in science and technology to come together for two weeks of leadership development training.

“It was a great honour for me,” Gatesi said. “It was my first time ever leaving the country, because the camp took place in Malawi, but it was a very good experience for me to meet girls from all over the world. We don’t share the same culture, but we share the same vision and same ambition.”

Being around these like-minded girls, who all had dreams of having an impact on the world through science, removed any doubt from Gatesi’s mind about becoming a cardiologist.

“From them, I gained the confidence that I could do that, and that I could convince even the other people that I could.”

Gatesi returned home with a renewed belief in herself. But she knew there were many other girls who hadn’t had an opportunity like hers, and might still be experiencing the same doubts that she had. She joined a group called Dear Doctor, which brings together students who have an interest in careers in medicine, as a way to give back to girls like herself.

“I came back to school wishing to help other girls who think that they can’t (be a doctor),” she said. “Joining the Dear Doctor club helped me to show them that they really can.”

As part of the club, Gatesi helped organize events where girls discussed challenges females face in the medical field, and invited doctors to speak about their careers. She also facilitated visits to nearby hospitals to meet with patients, and coordinated student internships with local health centers.

Now, as a member of UGHE’s majority-female, inaugural medical class, Gatesi brings the lessons she learned growing up to a university that prides itself on its commitment to equity. Here, she has found another community of people who share her vision, and said she feels optimistic about this new generation of leaders.

“Starting my journey at UGHE, where we are 20 girls and 10 boys, it has shown me that the future of Rwanda’s health sector is really bright because it has us—girls and boys who are passionate about becoming doctors and are not hindered by people’s mindset and view of gender.”