Meet Melquiades

It took four strong, kind-hearted volunteers nearly two hours to carry Melquiades Huauya Ore, lying waiflike in a bedsheet, from his home in El Agustino neighborhood in the hills of Lima, Peru, down a series of steep stairs to the closest health center. They did this every day, for several weeks, so that the then 20-year-old could take his medication against multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, one of the deadliest forms of the disease. After Huauya painfully swallowed a handful of pills, his generous volunteers would lay him gently back in the makeshift stretcher and hike back up the stairs to home.

For Huauya, the daily journey was exhausting. All he wanted was to stay at home, curled into a ball in his bed, resting. Yet, if he was to beat the disease and not infect his family, he had to make the pilgrimage.

Then, one day, something truly unexpected happened. Huauya was told there was a foreigner who wanted to see him. A lung expert from the United States. The young patient felt honoured to receive the special attention, and descended once again, this time to Sergio E. Bernales Hospital in Lima.

Dr. Jim Yong Kim, a co-founder of Partners In Health (PIH) and Harvard-trained epidemiologist, sat in the exam room and greeted Huauya in Spanish. While the frail young man slumped in a chair, his posture the picture of dejection, Kim began his exam. He spoke in a soothing tone and lifted his patient’s shirt to better listen to his heart and lungs. The image was shocking: Huauya was nothing but skin and bones.

The interaction between Kim and Huauya would become one of the most moving story lines in Bending the Arc, a 2017 documentary that tracks the 30-year evolution of PIH. But on that day, movie scenes were the furthest things from the minds of doctor, patient, and everyone in the exam room.

Under the watchful eyes of Kim and his community health worker, Huauya placed pills in his mouth, tilted up his head, and forced his Adam’s apple to bob up and down. Finally, the medication had passed, and his observers whispered words of encouragement.

The day remains emblazoned in Huauya’s mind. He was impressed by how Kim, a relative stranger who would go on to become president of the World Bank Group, had treated him with such compassion and kindness. He remembers the doctor pleading gently with him to stay the course: “’Please, don’t give up. Please, continue with your treatment.’”

An MDR-TB hotspot

Patients like Melquiades shouldn’t have existed in Peru. Up until the late 1990s, the country was considered a shining example of how to administer TB protocol outlined by the World Health Organization. The Ministry of Health ensured that patients were tested and treated for drug-sensitive TB, which can be cured with antibiotics such as Isoniazid and Rifampicin. The prevailing idea was that multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, or MDR-TB, simply didn’t have a chance to mutate within the population, because its easier-to-cure cousin got stamped out immediately. So when Kim and fellow PIH Co-founder Dr. Paul Farmer began visiting the country, they had no plans to tackle TB.

All that changed, however, when a Boston priest affectionately known as Father Jack died of MDR-TB in 1995. The priest was a good friend of Kim and Farmer’s, and it was at his request that they began working in Carabayllo, a slum north of Lima. The doctors discovered their friend had MDR-TB after he fell extremely ill and traveled back to Boston for care. A battery of tests revealed the truth.

Father Jack’s diagnosis came too late for a cure. But it sparked a renewed effort by Kim, Farmer, and staff at Socios En Salud (SES)—as PIH is known in Peru—to discover how entrenched MDR-TB was in Carabayllo, where most of their patients lived.

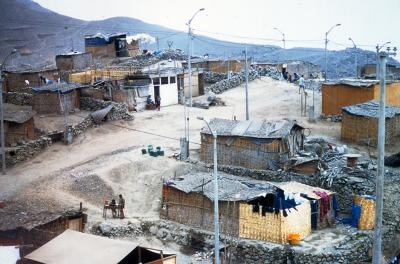

As it turned out, MDR-TB was everywhere. Carabayllo families live in close, cramped quarters in poorly ventilated homes, a dangerous breeding ground for an airborne disease. People are extremely poor and make difficult choices with scarce funds: Should they pay for medication with a day’s wages, or buy food for their children? And when it comes to transportation, most residents get around the city in public buses, where germs easily pass among passengers. All these factors, and more, combined to make the slum a hotspot for the disease.

A scene from Carabayllo, a hillside slum north of Lima, Peru, around 2001. Partners In Health began working here in the late 1990s, eventually focusing on the treatment of MDR-TB.

Courtesy of Partners In Health

A painful journey

Huauya can’t be sure how he caught MDR-TB, but he suspects it happened while riding public buses to and from work throughout the congested capital city. He remembers suffering from a persistent cough that didn’t go away after a couple of weeks of his mother’s homemade remedies. At a nearby health center in January 2002, a doctor took a chest x-ray and asked Huauya to provide a sputum sample to test for TB. The scan revealed a small manchita, or spot, on his lungs, and his test came back positive.

The 17-year-old was immediately placed on first-line antibiotics, which normally cure a regular case of TB in six months. But three months in, Huauya wasn’t feeling better. Further tests revealed he had MDR-TB, which required a different, more toxic line of drugs. The daily injections and handfuls of pills made him nauseous, gave him headaches, and spurred a bout of depression. For 10 months straight, he was hospitalized while doctors tried to get his condition under control.

“In the hospital, I got to the point of coughing up blood,” Huauya said. “Doctors said my lung looked like a colander. That’s how bad the situation was.”

Huauya’s hospitalization was hard on his two younger siblings, especially his 13-year-old youngest brother, Alex. Minors weren’t allowed into the TB wing. Yet Alex insisted on a surprise visit one day with their mother, Edifenia Oré Meza.

When Huauya heard Alex had come, he told his mother to bring his brother into the hallway and place him in a specific spot. He knew that if he peered through the moon-shaped window in the TB ward door, he’d be able to see Alex. His mother complied. Alex appeared in the appointed spot. And the two brothers enthusiastically greeted each other through the glass pane.

“That was one of the most beautiful moments for me,” Huauya said.

Eventually, Huauya was stable enough to return home and continue his treatment at a local health center. He was still incredibly weak, and relied on his family to help him get out of bed and do such simple tasks as go to the bathroom—and much harder ones, such as traveling down hillside stairs to the health center.

It was around that time Huauya met Kim and SES, whom he credits for connecting him with a community health worker. Twice a day for about one year, a middle-aged woman with a slight limp arrived at his family home to bring his medication. She stayed long enough to assure he’d swallowed his pills, then took off to the next patient’s home. There were many patients like him, Huauya learned.

“We really felt such great relief to avoid all of that” back and forth to the health center, Huauya said. He could finally rest and recuperate properly at home, and it was all to the credit of his community health worker, whose name—sadly—he couldn’t remember due to the tremendous strain of his illness and the powerful medication he took daily.

“I used to say to myself, ‘What a super human!’ She treated me as if I, too, were her son.”

Over the course of months, Huauya could tell the drugs were working. He started walking unsupported, his appetite returned and he regained weight, and his cough disappeared. Every two months, he sent sputum samples to the health center to be tested.

Several long years after he began MDR-TB treatment, Huauya—then 22 years old—was pronounced cured in July 2006. While a major milestone, it wasn’t the end of his journey. His battle with MDR-TB had taken its toll. The disease had eaten a section of his left lung, which had to be removed in 2007. Afterward, he spent one week at the health center and then returned home to recuperate.

“That’s Melquiades?”

Huauya had been sick for so long, good health felt like a luxury. “The only thing I thought about was making up all the time I’d lost with my family.” He worked on weekdays in a tienda, or store, to help meet the family’s expenses. On weekends, he took classes in computer informatics. For a year and a half, he even worked for PIH as part of the logistics team.

PIH staff remember Huauya as a shy, diligent type who kept to himself. Dalia Guerra, a nurse who has worked with PIH in Peru since 1997, met him when he was still undergoing treatment. She said he was always a polite, compliant patient who never asked for additional help, as other patients had.

Life returned more or less to normal. Normal, that is, for a young man who had narrowly escaped death. Then one day, Cori Shepherd Stern, producer of Bending the Arc, reached out to Huauya through SES after seeing old footage of him with Kim. They wanted to follow up on his story and see if he was open to an interview. The former patient agreed, honored to be part of the project.

Many months later, Huauya traveled to the United States, his first time in the country, to watch Bending the Arc’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017. He felt nervous sitting among PIH co-founders and Hollywood movie stars, and at the same time incredibly excited as the lights turned down and the documentary began.

There’s a poignant moment in the film, during an interview with Kim, when the filmmakers show him a clip of Huauya. The young man, then 31 years old, has healthy bronze skin. His face is filled out, and his broad shoulders tell how far he’d come since those long ago days at Sergio E. Bernales Hospital. Huauya smiled as he retold his story. At times, he seemed just as amazed as Kim that he had risen, like Lazarus, from his death-bed.

Kim was shocked at the sight of his former patient.

“That’s Melquiades?” he asked in disbelief. Tears welled in his eyes. “To think, we almost let him die?”

But, of course, they hadn’t. Huauya was there watching the film in the same room, a stone’s throw away from his former doctor.

“I really loved feeling the lived emotions of Dr. Jim Kim,” he said in a later interview. “To see that kind of reaction from him after seeing me—that was really beautiful.”

Huauya spent several days traveling in the United States before returning to his neighborhood in the hills of El Agustino, where he lives with his parents, beloved maternal grandmother (who still chides him to eat), and his younger sister and nephew. The Strongheart Group, a nonprofit advocacy organization that is working with the subjects of the film Bending the Arc to impact real change in the world, is training him to become an advocate for TB patients. Naturally shy when he was younger, he has found strength in sharing his story and has become an impassioned advocate for global health equity.

Looking back on his three years of treatment, Huauya remembers having—and then losing—faith that he would be cured. What pulled him out of the abyss, time and again, were the constant support and presence of his family, his community health worker, and PIH staff.

“There are many people who now are carrying the weight of TB treatment completely by themselves, without family or support. No one should be alone in this fight,” he said. “Everyone has the right to health. Everyone deserves equal access to health and the opportunity to reach their goals and fulfill their dreams.”