Each year, tuberculosis (TB) kills about 1.3 million people worldwide—that’s more deaths than HIV/AIDS and malaria combined. TB is the world’s deadliest infectious disease (though briefly eclipsed by COVID-19), killing someone every 20 seconds.

But, despite its massive fatality rate, TB rarely makes headlines.

In fact, many people in wealthy Western countries have no idea what TB is. Alternately, it’s considered a disease of the past, belonging in a history textbook.

But the disease that ravaged Europe and North America centuries ago remains a deadly, day-to-day threat in much of the world. And even though a cure exists, the disease continues to kill at unparalleled rates.

So why is TB still the world’s deadliest infectious disease? And why is it so little-known in the West?

What is tuberculosis?

To understand the gap in TB awareness, it’s crucial to consider how the airborne killer operates—and where in the world it’s most commonly found.

Tuberculosis is an airborne disease that spreads when infected people cough, talk, or even just exhale deeply. The disease typically attacks the lungs, but can affect almost any part of the body. Symptoms can be mild at first and resemble those of other conditions, like the common cold, making TB difficult to detect. If untreated, it can be fatal.

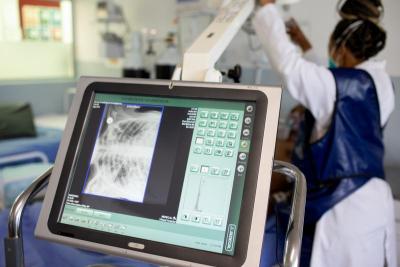

MDR-TB patient Khamokha Khamokha is seen by x-ray radiographer Mohau Nyapholi and MDR-TB nurse Mamahali Lethetsa at Botšabelo Hospital in Maseru, Lesotho.

Photo by Zack DeClerck / Partners In Health Canada.

TB has treatments and even a cure. But the path to a full recovery is long and arduous. Unlike diseases such as malaria, which can be treated within days, TB requires at least four months of treatment, and can take even longer to treat depending on severity and drug sensitivities. The standard regimen includes five drugs, which must be taken together each day. These drugs come with an array of side effects, such as nausea, skin rashes, and jaundice.

Although only a small percentage of people infected with TB end up experiencing the effects of the disease, its airborne nature, common symptoms, and long, arduous treatment regimen make it especially lethal in the places where it is most prevalent: impoverished countries with weak health systems.

‘A Neglected Disease’

Lesotho, a landlocked nation of around 2.1 million in southern Africa, has the highest TB incidence in the world—661 cases per 100,000 people, compared to 2.5 cases per 100,000 people in the U.S.

This data reflects global trends. Worldwide, more than 95% of TB deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. In fact, TB is often called a “disease of poverty.”

Dr. Afom Andom has studied TB for years, first as a graduate student, then as a technical advisor for Lesotho’s national health reform and now, as chief medical officer of PIH Lesotho. He has devoted much of his career to understanding why TB remains such a glaring issue in global health—and what can be done.

“TB is a neglected disease. It has been killing for centuries,” he says. “It’s been very persistent in countries with low socioeconomic conditions.”

The reasons for that persistence are many, but perhaps the most salient—and the most surprising—has to do with food.

“When you’re chronically malnourished, it affects your immune system,” says Dr. KJ Seung, senior technical advisor at Partners In Health and co-lead of endTB. “That makes you more likely to get infected if you’re exposed and less likely to control the disease if you’ve been infected.”

Mabuoang Sefole is screened for tuberculosis at Bobete Health Center, Lesotho.

Photo by Zack DeClerck / Partners In Health Canada.

TB drugs are also notoriously nauseating and taking them on an empty stomach can result in patients abandoning their treatment altogether.

Malnutrition isn’t the only reason why TB is typically linked to poverty. There are also issues like overcrowding, a lack of ventilation, a lack of transportation or time off work to reach clinics or hospitals, and so on.

To tackle TB at all—from testing to treatment to care—a strong health system is a must. Even prevention requires a level of infrastructure that has made TB difficult to curb. Simple measures that help prevent other diseases, like handing out bed-nets or condoms, aren’t going to work.

“TB is airborne,” says Seung. “You’re going to get it, you’re going to get exposed, and when you get exposed, you need a really well-functioning health system to get diagnosed and treated—and that just doesn’t exist.”

The Empathy Gap

Seung, who is based in Boston, has worked on TB across continents as co-lead of endTB, a clinical trial spanning seven countries that found safer, shorter treatments for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Through the years, he has seen stark differences in awareness levels of the world’s top infectious disease. In short, it depends on who you talk to.

“TB is really part of the culture of Africa, Latin America or Asia. People have more strong feelings about it compared to in the U.S. or Europe, because it just doesn’t exist here,” he says. “You don’t know somebody who has TB, or you might have to go back generations in your family. That same cultural cache just doesn’t exist.”

That “cultural cache” is reflected in health care systems, too, and how they respond to TB.

TB is so common in many countries that it’s part of primary care. In Western countries like the U.S., it’s instead treated as a rare disease; Americans with TB would have to see a specialist.

Less than 1% of Americans have TB. It’s not widely known, and most Americans don’t have to think about the disease on a regular basis, if at all, or know people who have had it.

These differences might seem more surface-level if they didn’t underscore a darker reality.

“If people are not interested in a problem, in the West, then it just makes all the effort to eliminate the disease globally very difficult,” says Seung.

For years, TB has struggled to get global attention, resources, and funding, despite ambitious targets like the UN’s goal to end TB by 2030.

“There is a huge disparity between the rich and the poor and that makes the disease persistent,” says Andom. “All the technologies, all the potent drugs, all the potent reagents are in high-income countries.”

Disparities between rich and poor emerge not only on the global level, but also within the countries most burdened by TB.

The communities where Socios En Salud provided free TB screenings are only accessible by boat.

Photo by Monica Mendoza / Partners In Health Canada.

In Peru, those most at-risk for TB are from vulnerable populations, including transgender people, migrants, prisoners, and people living in the Amazon rainforest.

“The only way to go to communities [in the Peruvian jungle] is by the river, and it’s difficult to transport all the [TB] equipment to the communities,” says Dr. Marco Tovar, director of health services at Socios En Salud, as Partners In Health is known in Peru.

In marginalized communities, TB is far from the only killer. There’s dual epidemics of TB and COVID-19, or TB and HIV; drug-resistant forms of the disease, like MDR-TB or XDR-TB, and then there’s poverty, making actions as simple as getting to a clinic or eating a healthy meal an insurmountable challenge.

Changing the Narrative

With all the challenges and complexities of TB, it might be easy to think of the disease as inevitable, as some natural state of affairs. That’s a narrative that Dr. Maxo Luma is fighting against.

“1.3 million die every year of a disease that is totally curable,” he says. “That’s not normal.”

TB is not inevitable. When health systems are strengthened, it is preventable, treatable, and even curable.

Luma has seen this first-hand in Liberia, where he is the executive director of PIH’s country program.

Before PIH began its work in the West African nation of around 5 million, the only health center for MDR-TB was in Monrovia, the capital. For those living in the rural southeast of Liberia in Maryland county, traveling there could take up to 4 days and, during the rainy season and flooding of roads, could take weeks, if it was possible at all.

Since it began working in Liberia in 2014, PIH has treated thousands of patients with all forms of TB including hundreds with MDR-TB. In 2017, PIH opened the first-ever decentralized regional hub for MDR-TB care in the southeastern part of the country, at J.J. Dossen Memorial Hospital, in partnership with the Liberian government.

Similar progress has emerged in Lesotho.

PIH began its work in the southern African nation in 2006; the following year, it opened Botšabelo Hospital, one of the first MDR-TB treatment hospitals in Africa and the only one in Lesotho. The hospital has since become a model for MDR-TB care across the continent.

Treatment supporter Rethabile Setenane administers medication to Lerato Leqhaloha at the Malaeneng MDR-TB halfway house in Maseru, Lesotho.

Photo by Zack DeClerck / Partners In Health Canada.

PIH’s TB work in Lesotho and elsewhere has tackled another key element in preventing the disease: testing.

While treatment is often put in the spotlight, an effective TB response starts before a patient is sick. To get treatment and recover from TB, people first have to know that they have it. Globally, around 30% of TB cases are never diagnosed or treated. In Lesotho, that percentage is much higher, around 63%.

Most TB diagnoses in Lesotho happen at district hospitals, due to a lack of diagnostics at the health center level. Health centers typically transport samples to hospitals on scheduled days, resulting in delays between when patients are tested and when they are diagnosed.

Starting in 2020, PIH began working with Lesotho’s Ministry of Health to make diagnostics available at the health center level in seven rural, hard-to-reach health facilities, as part of the Rural Health Initiative.

Now, at PIH-supported health centers, patients can get test results within 1-2 hours and return home with a diagnosis and treatment plan, thanks to GeneXpert machines and digital x-ray equipment.

Progress has been made on a global level, too. With the endTB trial, PIH and partners found safer, shorter drug regimens for MDR-TB patients. PIH recently joined clinicians and TB activists to call on pharmaceutical companies to drop patents and prices to make TB care more accessible.

But there is still much more work to be done—both in raising awareness and in making essential funding and resources available where they are most needed.

For Luma and many other experts, the fight is not just medical—it’s moral.

“It doesn’t have to be in our backyard to make it our problem. We are a global village,” he says. “I think more people need to be aware so we can change the narrative around TB…It is time for all of us to finally unite around ending this disease.”

Originally published on pih.org