In a lecture published this week in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Paul Farmer digs into the past to draw lessons for the future. In “Chronic Infectious Disease and the Future of Health Care Delivery,” he argues that successes from the world’s response to tuberculosis and HIV can be applied to improving care for chronic illnesses, which make up an increasing burden of disease in poor and wealthy countries.

Here are five highlights from the lecture:

- In an era of antibiotic resistance and chronic disease, medicine must take on the work of bridging the “know-do gap”—the often-neglected work of getting effective therapies (the “know”) to people who need them (the “do”).

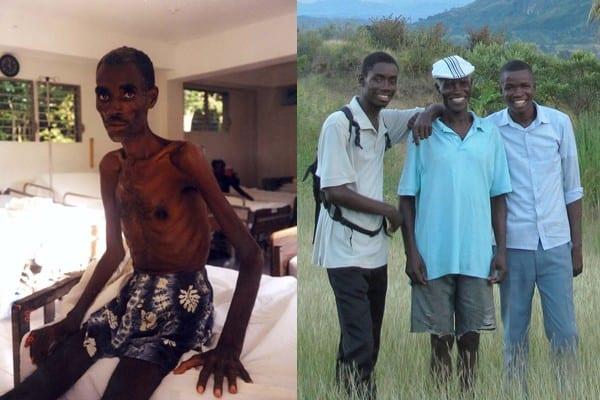

- No disease should be considered “untreatable.” In treating HIV with antiretroviral therapy in Haiti, Partners In Health resolved so-called obstacles to treatment by employing community health workers to deliver complex drug regimens and improve patients’ access to social support, such as food and housing. Farmer writes, “‘Untreatable’ often really means difficult or costly to treat, just as ‘resistant’ sometimes means resistant to our best efforts to deliver care.”

- Prevention and treatment are complementary, not in competition. With AIDS, people were reluctant to learn whether they had a disease for which there was no treatment. When patients learned that they could be treated for the disease, and mothers could prevent the spread of HIV to their children, demand for HIV testing and prevention services increased.

- With AIDS, debates about feasibility were really about funding. Delivering antiretroviral therapy to the millions of people who couldn’t afford it was feasible, but required a financial commitment from wealthy countries—which came about in the form of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and PEPFAR.

- Funding designated for specific diseases, such as HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, can strengthen primary care to tackle a broad range of illnesses.

United States, take note. As many wealthy countries have minimized deaths from infectious disease, the growing threat is chronic disease—hypertension, diabetes, and cancer, for example—which require ongoing care and attention to social needs such as access to healthy foods.

Farmer writes, “The know-do gap is readily visible in the United States, where resources are plentiful but outcomes are uneven and health disparities persist …. Our system does a poor job of linking hospital-based care to that delivered in clinics, homes, or workplaces. Care delivered with the help of community health workers, and attuned to the social needs of the patients, is meant to do just that.”

He concludes, “If only we could develop the right community-based and equitable delivery platforms in advance, we could spare our patients a lot of suffering, and ourselves a lot of headaches and acrimony.”