‘Mountain Kingdom’ of Lesotho Making Huge Strides with Health Reform

All photos by Cecille Joan Avila / Partners In Health.

Every three months or so, Atlehang Seisa saddles up.

The lead nurse at Mapheleng Health Center in a bucolic corner of Lesotho, Seisa joins a small team of doctors on quarterly trips by horseback, to villages over the hills. The team stays at the remote villages for a week at a time, providing health services ranging from HIV testing to outpatient care. Some of the staff come from Mapheleng, which is supported by Partners In Health (PIH), and others come from Maluti Adventist, the only hospital in the region. They provide all the care they can over each weeklong stay, because they won’t be able to come back for months.

Mapheleng, itself, is not easy to reach. From the nearest paved road, the health center lies at the bottom of a long, rutted dirt road that winds down steep, green hillsides and is crossed by several creeks. The views of broad valleys sweeping toward mountains on the horizon are jaw-dropping. Traversing those mountains on horseback seems incredible.

But on a February day at Mapheleng, during late summer in Lesotho and across southern Africa, the arduous rides are the last thing Seisa mentions. He has other concerns. The health center serves about 6,200 people across 28 villages, including those reached by horse. Difficulties are many. Sometimes, for example, Mapheleng has power shortages when its solar panels lose their charge after a couple of cloudy days.

“We don’t have a way to store power,” Seisa said. “It can be quite a challenge in the winter.”

But on this particular day, the sun is shining, the lights are on and the chatter is loud. Several families wait for outpatient services in a central reception room. Just outside the front entrance, expectant mothers talk with village health workers (VHWs), who live in surrounding communities and help their neighbours access health services and maintain treatment.

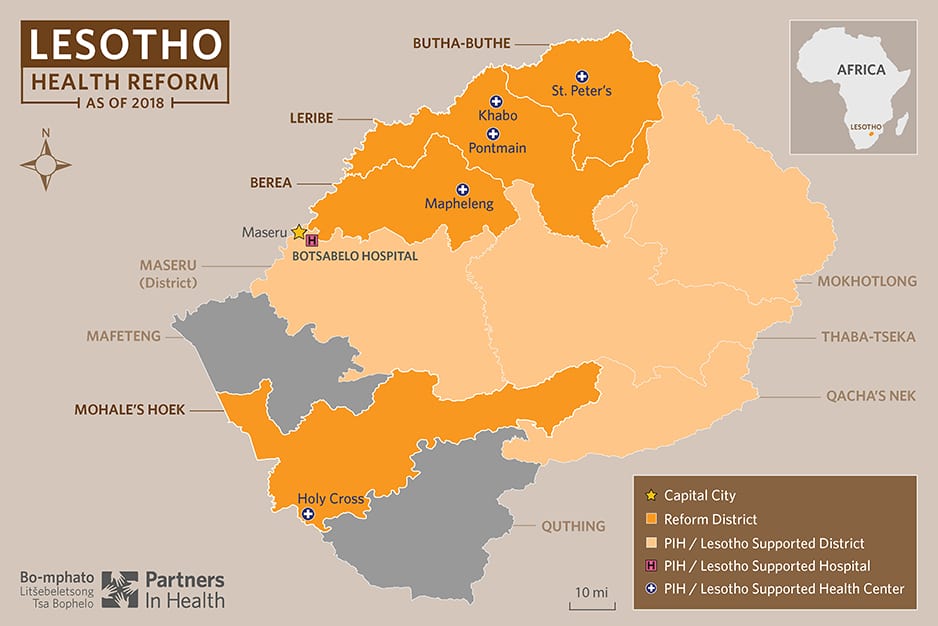

It’s a scene replicated at 72 health centers in Lesotho, where a sweeping health reform has brought about transformative change in just four years. The reform is combating some of the world’s highest rates of HIV and TB, vastly improving maternal and child health, and reshaping how care is delivered, from mountain villages to urban centers.

And it’s finding resourceful ways to meet challenges, such as supplying delivery packs to health centers so inconsistent supplies of electricity—such as Mapheleng’s—don’t prevent pregnant mothers from having sterile, safe environments for childbirth.

Partners In Health (PIH), known locally as Bo-mphato Litsebeletsong Tsa Bophelo, is supporting the reform as the primary technical advisor to Lesotho’s Ministry of Health.

The goal is to scale the reform nationally, from four pilot districts to all 10 districts across the country, blazing a trail toward universal health coverage in the vibrant, largely agricultural, and stunningly beautiful land known as the Mountain Kingdom.

Over two weeks in February, a whirlwind tour of PIH’s work in Lesotho included visits to patients’ homes and rural health centers like Mapheleng; conversations with HIV patients, VHWs, and new mothers who were able to deliver their babies safely; and even a meeting in the highest halls of government, with Lesotho’s prime minister.

The firsthand look at the reform—conducted by PIH staff, for this report—revealed remarkable innovation, dedication and achievements, along with daunting challenges brought by rapid growth in patient demand and limited resources.

But above all, one thing was clear: Lesotho is building a health system that could become a model for impoverished countries around the world.

“We hope this reform will encapsulate PIH’s global approach for actualizing universal health coverage,” said Dr. Abera Leta, executive director of PIH in Lesotho. “But we are far away from reaching the universal health coverage target, and that is where we need to fill the gap. We still have to go a long way to really reach many segments of the population.”

Ebb and flow

The 72 health centers involved in the reform and their surrounding “catchment areas”—meaning, the populations they serve—reach about 40 percent of Lesotho’s 2.1 million people, the Basotho.

Their home is a high-altitude country that’s a little over half the size of Nova Scotia and entirely surrounded by South Africa. All 10 of Lesotho’s districts touch some part of the border.

Many Basotho cross that border frequently. Unemployment is high in Lesotho, and better luck for mining, trucking, construction and manufacturing jobs can be found in South Africa. As a result, many adults, particularly men, stay in South Africa and work for weeks or months at a time, returning only sporadically to their families and homes in Lesotho.

Mpho Phoofolo, for example, said her husband works in construction in South Africa, and sometimes returns only twice a year to their one-room home in the Berea District village of Ha Matoeba.

Phoofolo, 27, held her newborn daughter, Itumeleng, as she talked about her family. Phoofolo is HIV-positive and has been on antiretroviral therapy, or ART, for five years. She gets treatment, as well as services for Itumeleng and her 5-year-old son, Katleho, at Mapheleng. The health center is about a 10-minute walk from Phoofolo’s home, meaning Seisa can get there with no need of a saddle.

A green bag containing Phoofolo’s medicines sat atop a pile of clothing beside her bed as she held Itumeleng. Outside, Phoofolo’s mother, Mamoletsane Phoofolo, stirred a soft porridge called “lesheleshele” in a covered pot over a bed of smoldering ashes. She lives nearby, and Phoofolo said neighbours often help out, too, by fetching water for her family. She didn’t know when her husband would return home.

Border crossings dot the region and usually are busiest in the capital, Maseru, which lies in a west-central part of the country known as the lowlands.

Traveling north from the capital, a two-lane highway passes through three reform districts in a row: Berea, then Leribe, and then Butha-Buthe, moving progressively northeast and gaining altitude, from the lowlands into the highlands.

To the south of all those regions lies Mohale’s Hoek, the fourth pilot district for the reform. The district’s mountainous topography and large population of transitory miners contribute to high rates of HIV and TB. Airborne diseases like TB can thrive in crowded, poorly ventilated conditions such as mines. Workers who contract HIV or TB in mines, or from infidelity while away from home, are prone to bringing the diseases back to their families and communities.

Dr. Mahlape Tiiti, district health manager for Mohale’s Hoek, said about 29 percent of the district’s 170,000 people have HIV, the worst rate in Lesotho.

Nationwide, about 25 percent of Lesotho’s adult population has HIV. That percentage is the second-highest in the world, behind only the nearby Kingdom of eSwatini, which was called Swaziland before a name change in April.

Tiiti said people who live two hours or more from health services—common in Mohale’s Hoek, and many parts of Lesotho—are less likely to be tested for HIV, or to consistently access treatment.

The Ministry of Health and PIH are working to change that from the ground up, by building a strong primary health care platform, decentralizing care and improving district management, staffing, systems and supplies.

Dr. Afom Andom, PIH’s lead technical advisor for the reform, said PIH’s role also includes funding a primary health care coordinator in each of the four districts, along with one pharmacist and one data clerk per district, to improve communication channels, medicine distribution and medical record-keeping.

Tiiti said the increased structure and communication is paying off.

“I think one thing that the reform has done is establishing district health management teams, which oversee all the health issues in the districts,” she said. “Initially, there was separation of services. The hospital was on its own, the district management team was on its own…there was really no connection. Each entity had its own separate management.

“But the reform has combined them together, and I think that has benefited us a lot,” Tiiti continued. “Because now, communication and working relations are much better. Because each department is represented on the management team, the job is much easier.”

The work is yielding clear results.

The number of people receiving HIV testing in the reform’s four pilot districts, for example, has more than quintupled, rising from 61,560 people tested in 2013 to 327,617 four years later.

Correspondingly, more testing has meant more treatment: The number of HIV patients enrolled on ART has more than doubled, from 7,364 in 2013 to 15,324 in 2017.

And, crucially, more than 90 percent of all people diagnosed with HIV now are receiving sustained treatment.

Dr. Nyane Letsie, director-general for the Ministry of Health, said those impacts show why Lesotho’s health reform must continue moving forward.

“We don’t have any option except to roll out the reform—and this will save many, many, many more lives,” Letsie said in February, at a meeting with ministry leaders and PIH staff in Maseru. “Our dream is to make sure the approach now is standard, and all the districts are able to maintain a high quality of care.”

Safe deliveries

The reform has made maintaining a high quality of care an emerging challenge for facilities such as St. Peter’s Health Center, where demand for services is rising.

Situated on the side of a mountain in the rural, highland district of Butha-Buthe, near Lesotho’s northern edge, the small St. Peter’s campus is overflowing. The health center serves more than 8,200 people, from 43 villages across the region. Many of those people travel for hours to reach St. Peter’s, crossing rivers and climbing mountains, most often on foot. Staff treat patients for HIV, tuberculosis, diabetes and more, while providing services ranging from child immunizations to prenatal and postnatal care, deliveries and general checkups.

They do all of that with limited resources, and very limited space.

Masefako Ntjabane Liotlo, manager and lead nurse at St. Peter’s, said the health center’s on-site staffing includes two nurse assistants, four midwives and five counsellors.

Their facilities include a main building surrounded by several smaller, one- or two-room buildings, on a sloped site with little room for expansion.

Mpai Rutsoa, the primary health care coordinator for Butha-Buthe District and a professional nurse, said the tight conditions at St. Peter’s likely are a result of the center’s initial design, which predates the reform. St. Peter’s was built to provide one or two services, she said, rather than the many services now offered there.

“It’s kind of a supermarket approach,” Rutsoa said. “So, they have to be creative, to manage their space.”

The cramped quarters can lead to difficult choices. Liotlo said the health center offers services for children younger than 5 only on Thursdays, while cervical cancer screenings are offered on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

Blood draws for HIV patients also occur only on Thursdays, in a room otherwise designated for postnatal care. That means trays of samples sometimes sit on beds where, at other times, women rest after giving birth.

Liotlo, a short-haired, bespectacled woman who exudes steadiness and experience, would prefer that all those services were provided daily, and that she had a large space dedicated solely to maternal and child care.

Offering services for young children just once a week, she said, “means that some of them, we miss them.”

On a sunny Thursday morning in February, several women sat outside the front entrance and talked while their children played nearby. Litsoanelo Rosalia Lerapa said she had been at St. Peter’s since 8 a.m., after walking an hour while carrying her 2-year-old son, Mokhomotsi. As midday neared, she still was waiting for his checkup.

But Lerapa, 22, said the free services she and her son receive at St. Peter’s are invaluable. She stayed in the health center’s maternal waiting home for about a month before giving birth to Mokhomotsi, because nurses said he might come early and she needed to be near the St. Peter’s delivery room when labour began.

Mokhomotsi, about 2 years and 7 months old that February day, was healthy and active, and ran around the health center in Superman sandals.

There are just two beds, and one small bathroom, in the maternal waiting home where Lerapa stayed. A mattress often is placed on the floor between the beds, for a third mother. Demand has risen so much that when the waiting home is full, some expectant mothers sleep in other buildings at St. Peter’s.

Liotlo said the number of deliveries at the health center has risen dramatically since the reform began, from 12 in 2014 to 82 in 2015, 97 in 2016, and 89 last year.

A key aspect of Lesotho’s national health reform is encouraging and enabling expectant mothers to deliver their babies in a health facility. Facility-based deliveries are much safer than delivering at home, where—should complications arise—there is no access to medication, a blood bank, or trained professionals to perform emergency cesarean sections.

As the reform enters its fifth year, the number of facility-based deliveries across four pilot districts has doubled, from 6,012 in 2013 to 12,109 in 2017.

That increase has a clear driver: Before the reform, just 2 percent of the 72 health centers in those districts were providing facility-based deliveries.

That number now has reached 95 percent, and every one of those health centers now has a maternal waiting home. If complications arise, PIH funds transportation to the nearest hospital.

Home by home

St. Peter’s reach extends far beyond its busy campus.

Based at the health center are 68 village health workers, or VHWs, who go door to door, and family to family, to ensure every need is met in the area. VHWs across Lesotho’s reform districts monitor patients’ treatment, help them keep up with medicines and refer them to health facilities when needed, often providing free transportation.

“We are nothing without VHWs,” said Jeannett Letsoso, lead nurse at Pontmain Health Center in Leribe District, just south of Butha-Buthe. “Without them, we are doomed.”

As part of its role in the reform, PIH has installed a VHW coordinator at each of the 72 health centers across the four pilot districts, to improve management and structure of the VHW system. VHW supervisors are just below the coordinator level, adding another layer of local oversight.

Mathato Tšolele, 38, is a VHW supervisor at Pontmain. The health center sits atop a large hill in a big-sky part of Leribe with wide open spaces and vast tracts of farmland, where cornfields often stretch to the horizon and villages can span huge areas. Pontmain serves about 8,200 people across 52 villages, a catchment area very similar to St. Peter’s further north, and has 116 VHWs.

Tšolele oversees 11 of those VHWs. They serve 670 households across five villages, including her own village of Lumela.

“Lumela” also is the customary greeting in Lesotho’s language of Sesotho. The first “l” in the greeting is pronounced as a “d” sound, as in, “doo-meh-lah.”

Additionally, “Sotho,” in all its uses, is pronounced “sue-too,” as in “Luh-sue-too,” for the name of the country.

Tšolele said she has been a VHW since the reform began, in 2014. Pontmain administrators notified the chief in her area that a VHW was needed, so the chief held a public gathering, where Tšolele’s neighbors elected her to serve them. That elective practice is common with VHWs across the reform districts.

Tšolele, wearing a white-and-blue Pontmain Health Center hat and matching Converse sneakers, spoke in Sesotho as public health nurse Keneyoe Kali translated to English.

One of her most memorable patients, she said, is a 62-year-old woman who had a relapse of TB and needed daily injections in her posterior. The patient, Tšolele said with a rueful smile, was not very happy about treatment.

The woman lived in Lumela village, but far enough away to make it a substantial daily trip for Tšolele. She complained every time she saw Tšolele approach, grumpily resisting the injections.

But Tšolele persisted, visiting her patient for 56 straight days. The woman recovered, and became free of TB after a lengthy battle with the disease.

Now the two chat happily whenever they see each other, Tšolele said, and have become lasting friends.

Tšolele’s dedication is one example of why treatment for TB, the world’s deadliest infectious disease, is seeing broad success from the reform.

While 108 people in the four pilot districts were cured of the airborne disease in 2013, 833 were cured in 2017.

That’s a sea change in Lesotho, which had the world’s highest TB incidence rate as recently as 2014. Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) showed that in that year, when the reform began, Lesotho had a TB rate of 852 people per 100,000.

The latest WHO data, from 2016, shows that Lesotho’s TB incidence rate has fallen to 724 people per 100,000. That rate is the world’s second-highest, behind South Africa.

The same outreach that is improving TB care is having similar effects on maternal health in the area around Pontmain. Letsoso, the health center’s lead nurse, said Pontmain now is conducting about 20 deliveries a month, compared to none before the reform. Staff also are seeing more pregnant women in their first trimester, leading to greater successes with prenatal care.

“Since the reform, we’ve had much fewer maternal deaths,” Monica Mpala, primary health care coordinator for Leribe District, said while holding the grab handle above the passenger seat of a truck bouncing along the road to Pontmain. “The reform is like a wake-up call for everyone.”

‘Success challenges’

Dr. Abera Leta, PIH’s executive director in Lesotho, said that while the national reform is facing challenges, they primarily are “success challenges” from the rapid growth in services.

“When people start to access care, you have to provide a lot of supply,” Leta said. “When you compare where we were to where we are, it is quite a change.”

PIH is doing everything it can to meet that demand.

“Every day, we receive a lot of calls, emails and visitors,” he said. “We deal with all of them, to make sure the caller gets what we can offer, and what the system can offer. Whatever is happening, we want to help them. We want to deliver on our promise.”

PIH CEO Dr. Gary Gottlieb was on hand for the staff meeting, and applauded the achievements of all those assembled.

“You all have been extraordinarily flexible and innovative,” Gottlieb told the room. “You are truly a blessing, to this country and to PIH. Lesotho is becoming a world-class story in transformation.”

That transformation goes far beyond the data and numbers. The impacts are societal.

Dr. Letsie, the Ministry of Health director-general who has been a leader in the ministry’s collaboration with PIH, said at Motebang Hospital, in Leribe District, that the reform was stabilizing health services across the entire region.

She told Ministry of Health, PIH and district health leaders that patients who previously had flooded Motebang from outlying areas and neighbouring districts were now, instead, accessing services at health centers near their homes. She said that change was easing the burden on the hospital and its staff, and spreading care to communities that, before the reform, had none.

The trend also was changing health data across several districts, Letsie said, in ways that couldn’t yet be analyzed in isolation, and would only truly unfold in months and years ahead.

Additionally, Letsie said, the reform’s increased support and structures were proving that local health centers can retain local doctors, which is empowering them and reinforcing community support for health care.

As more and more people saw their family members, friends and neighbours receiving high-quality care, overall trust in local health systems—and thereby, use of those systems—was increasing.

“What the reform has brought is that we have changed our district and local structures,” she said. “This is bringing big changes to communities, and to people’s lives.”

‘Don’t give up’

The reform’s impacts are recognized at the highest levels of Lesotho’s government.

During a visit to Lesotho in early February, Dr. Gottlieb heard strong praise from several Ministry of Health officials such as Letsie, and also was invited to speak about the reform in person with Lesotho Prime Minister Thomas Motsoahae Thabane.

The two met for a conversation of about 15 minutes on Feb. 6, in a formal seating room on the top floor of a Maseru government building used by Lesotho’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Relations. The beginnings of an evening thunderstorm rumbled outside the large windows as the sky darkened, but the mood of the conversation was bright.

“I must say that over these past few years, there has been remarkable progress,” Gottlieb said to Thabane. “The reform districts have awakened.”

Gottlieb then spoke about Khabo Health Center in Leribe District, where, as at so many other health centers under the reform, maternal deaths are falling and facility-based deliveries are rising. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV also is falling, he added, helping Lesotho move toward the goal of “ridding the country of HIV.”

The ministry and PIH have placed HIV testing, counselling and ART as key priorities for the reform. The efforts are working: More than 90 percent of all people diagnosed with HIV in the four pilot districts now are receiving sustained ART.

Thabane was reflective in his remarks. The 78-year-old statesman has been through decades of political battles, of wins and losses. His career began in the mid-1980s, when he served as principal secretary for health under Lesotho’s second prime minister, Leabua Jonathan. Thabane became prime minister himself in 2012 but left power three years later, when his All Basotho Convention party lost parliamentary elections.

He returned to power, and to Lesotho, in June 2017. He had been living in South Africa in the interim.

“We are now in a period where we should really be doing the right things,” he said to Gottlieb. “We have always had this bad name, of being ‘the dark continent,’ but it’s not dark now.”

The prime minister then added a joke.

“It’s going to be dark in an hour or two from now, but we’ll switch on the lights,” he said, gesturing at the sky outside. “But Africa as the dark continent—we don’t want it, and we don’t deserve it.

“But the good thing is that in that process, and in the efforts that we make, there is so much goodwill and friendship internationally,” Thabane continued. “And all we have to do really is…embrace it. Embrace it for the benefit of those who are really suffering. And not because they are careless, not because they have done anything wrong, but simply because the environment around them, that they were born into, was not favourable.”

The two leaders spoke more, about political conditions, health care and, on a personal side, their shared experiences with aging. Thabane, whose head is shaven, jokingly said that he cuts his gray hair so people think he is younger—and then advised Gottlieb to do the same, spurring laughter in the room.

Gottlieb then said that PIH is, “excited to tell the world about the progress that we’ve made here in Lesotho. To tell the people of Lesotho in any way that you think is right. To tell the world so that we can get more support and more funding to be able to move this forward, so that we can move from four districts to 10 districts, so that this platform becomes the platform for this country for a long, long time into the future.”

“Fantastic,” Thabane replied.

The prime minister then urged Gottlieb and PIH to continue with reform efforts.

“My dear friend, don’t give up,” Thabane said. “Don’t give up. You have friends in many, many places. And you have a friend in us.”

Article originally posted on pih.org