Forbes: Countering Failures Of Imagination: Lessons We Learnt From Paul Farmer

Contributor: Madhukar Pai

Posted on October 21, 2022

Original Article Published with Forbes

Written by Dr. Madhukar Pai: Paul Farmer, physician, activist, academic, humanitarian, and teacher died in Rwanda on February 21, 2022. Few people in the field of global health have had a bigger impact than him. After his death, people all over the world took to social media and blogs, and wrote about how his life inspired them. My favorite was this tweet from Arcade Fire, the Canadian rock band: “Paul Farmer changed our lives forever. He showed us how to work harder for others than for yourself. He was the punkest mother fucker WE ever met.”

I’ve had the privilege of interviewing him twice, once on stage in 2018 when he visited my university (McGill University), and, more recently, for Forbes, about his 2020 book on Ebola in West Africa. Both times, I was blown away by how much time Paul gave me, and the words of encouragement he had for my work on tuberculosis.

Recently, for a global health course that I teach at McGill, I tried to summarize my big learnings from Paul, and posted that as a tweet. Inspired by the responses to my tweet, I interviewed 20 people from around the world, asking them for their biggest learnings. By sharing them in this post, we hope to keep his legacy and teachings alive.

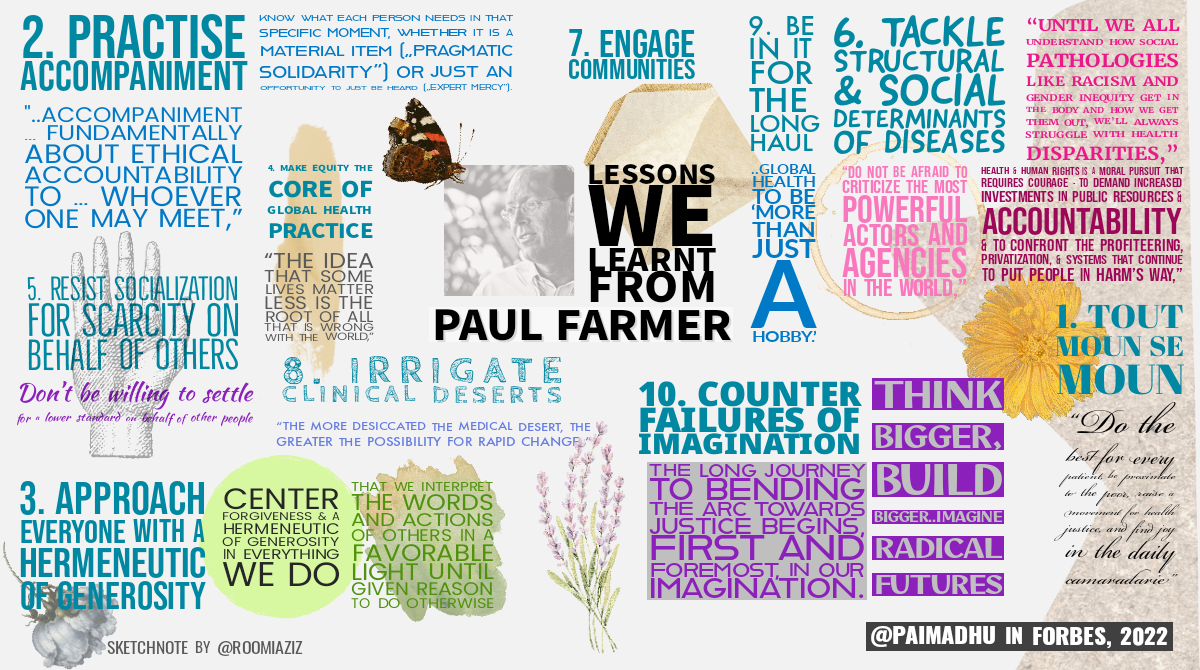

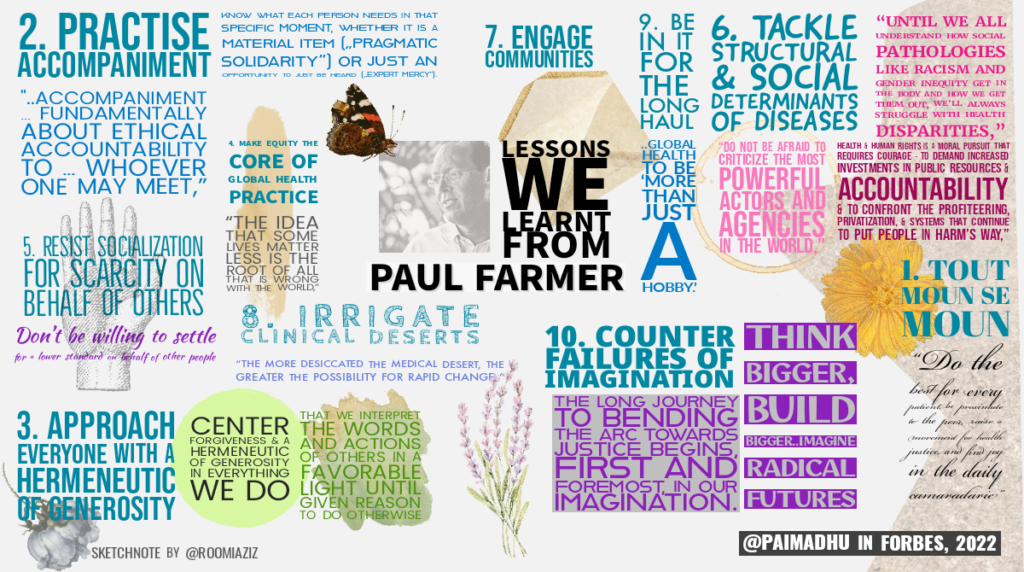

Lesson 1: Every person matters

Paul strongly believed that all people, no matter who they are or where they are, deserved healthcare and support. In Haitian Creole “tout moun se moun” roughly translates to ‘every person is a person.’

He saw health as a fundamental, non-negotiable human right. “If access to health care is considered a human right, who is considered human enough to have that right?” is a particularly famous Paul Farmer quote.

“Paul’s love for humanity, regardless of an individual’s background or characteristics, his complete disregard for what he called a scarcity mindset for others, and his deep and genuine care for those that are suffering have shaped how we practice global health,” said Agnes Binagwaho, Vice Chancellor of the University of Global Health Equity (UGHE) in Rwanda.

“Do the best for every patient, be proximate to the poor, raise a movement for health justice, and find joy in the daily camaradarie,” are the biggest lessons Joia Mukherjee, Chief Medical Officer, Partners In Health (PIH), learnt from her years of work with Paul.

For Mohamed Bailor Barrie, Executive Director of PIH, Sierra Leone, Paul taught him to “listen attentively and be empathic, not to say “NO” to whatever patients asked us, but to figure out a way with them.”

“Understanding the needs of the most impoverished people requires working in close proximity to them and in pragmatic solidarity. For me – this philosophy contributed to my continued clinical work as well as my research/public health work,” said Louise Ivers, infectious diseases physician and Director of the Harvard Global Health Institute.

Lesson 2: Practice accompaniment

“Amongst the many lessons I’ve learned from Paul, what inspired me most about Paul was his practice of accompaniment and his unique ability to meet people exactly where they were – no matter where that was – and sit beside them, with them, accompanying them,” said Sheila Davis, Chief Executive Officer, PIH. “Paul taught us – by modeling accompaniment himself – that our lives are in service to others and that the best things we do in life are for others, and that we must stand for them and with them,” she explained.

“One of the most valuable lessons I learned from Paul is the meaning and importance of accompaniment,” said Katherine Kralievits, who worked with Paul as his Chief of Staff for many years. “I was fortunate enough to accompany Paul in a variety of settings—from Harvard to Haiti to Rwanda to West Africa—and the role of accompaniment looked different across every setting. Paul had a gift of knowing what each person or patient or student needed in that specific moment, whether it was a material item (“pragmatic solidarity”) or just an opportunity to just be heard (“expert mercy”). In every moment, Paul exuded patience, warmth, and love, and I continue to call on his memory when accompanying loved ones, friends, and colleagues in this “new normal” without Paul,” Kralievits added.

“Of all that he’s left me, it is the lessons of accompaniment that continue to resonate with me most and that will continue to guide both my concept of political struggle and my own most intimate sense of what it means to be in community with others,” said Eric Reinhart, an anthropologist of law and public health, and physician at Northwestern University. “He showed me that accompaniment isn’t an abstraction nor is it only about community health workers or healthcare delivery; it’s fundamentally about ethical accountability to one’s friends, students, patients, and whoever one may meet,” he added.

Lesson 3: Approach everyone with a hermeneutic of generosity

“An enduring lesson from Paul is the importance of a “hermeneutic of generosity,” or a “H of G,” which demands that we interpret the words and actions of others in a favorable light until given reason to do otherwise,” said Anne Sosin, Policy Fellow at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College.

Michelle Morse, Deputy Commissioner at NYC Health Dept and an Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School, was mentored by Paul, who taught her to “center forgiveness and a hermeneutic of generosity in everything we do.” In other words, generosity has to be a first principle, a guiding and foundational value, that shapes our approach to all things, explained Morse.

Lesson 4: Make equity the core of global health practice

It is impossible to read Paul’s books without encountering the word equity on every other page. “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world,” is another famous Paul Farmer quote. He pushed everyone to provide a ‘preferential option for the poor’ in health care.

“Do we want global health, as is practiced from universities across the globe, to be radically different from colonial health or tropical medicine? If so, then let’s stop referring to it as “global public health” or “global health security” and start calling it “global health equity,” he told me in my 2021 interview.

“Paul fought every day of his life to right what he considered the greatest wrong: the idea that some lives matter less than others,” said Aaron Berkowitz, a professor of neurology at UCSF, and author of One by One by One in which he tells the challenging stories of his attempts to follow in Paul’s footsteps caring for patients with brain tumors in rural Haiti.

“No lives matter more than others, provide healthcare equitably” is a key lesson Joselyne Nzisabira, a Rwandan Medical student at the University of Global Health Equity, learnt from Paul. The night before Paul Farmer died, Joselyne read him a poem she wrote for him. In her poem, she thanked Paul for choosing to be a health activist in a world full of inequities.

“The main lesson that I obtained from Paul is that humanism is unveiled when we care for each other,” said Daniel Bernal, a physician at the Tec de Monterrey School of Government and Public Transformation, in Mexico. “Feeling and understanding the suffering of others leads us to treat everyone as we would treat our own kind. This inevitably gravitates our focus of action towards poor, for they are the most affected by structural violence,” he elaborated.

“Fundamentally, Farmer believed in equity and that manifested in his mission to provide healthcare to those without access. It drove all that he did. Part of his legacy to me is that one person can have a huge impact,” said Mimi Alkattan, an environmental engineer, and a Fulbright Student Researcher, and former Peace Corps volunteer.

Lesson 5: Resist socialization for scarcity on behalf of others

Paul believed that global health is ‘socialized for scarcity on behalf of others.’ Countries under-invest in health, and, because of the under-investment, choices are often made between prevention and treatment; between disease A versus B; and between disease control versus clinical care. The scarcity, zero-sum game mindset also promotes the ‘control over care’ approach.

“Don’t be willing to settle for a lower standard on behalf of other people,” is a big lesson that Jennifer Furin, a physician-anthropologist and TB expert, learnt from Paul, who mentored her for many years. “We privileged people do this all the time—settle for things that are lower quality for others that we would never accept for ourselves. Paul taught her to always ask “what would this person say if they were sitting here too?” and then try and move things in that direction,” she explained.

An excellent current example of setting a lower standard for others is our acceptance that rich nations deserve unconstrained access to Covid-19 vaccines, bivalent boosters and anti-viral treatments, while people in low-income nations should settle for much less or nothing. Everything is possible for the rich and privileged, but very few interventions are ‘cost-effective’ in low-income populations. This apartheid logic has killed millions already.

“Paul taught us that concepts of ‘sustainability’ and ‘cost-effectiveness’ were based on a flawed notion that resources were limited, fixed or scarce, when in fact there are more resources now than at any time in human history, they are just inequitably distributed,” explained Aaron Berkowitz.

“Many of us enter medicine hoping to change the world; Farmer actually did it. He did it because he refused to believe it wasn’t possible,” wrote Lisa Rosenbaum, a physician and national correspondent for the New England Journal of Medicine. Her article “Unclouded Judgment — Global Health and the Moral Clarity of Paul Farmer” is a brilliant tribute to Paul’s life and legacy.

Lesson 6: Tackle structural and social determinants of diseases

In many of his books (e.g. Infections and Inequalities, and Pathologies of Power), Paul emphasized that epidemics are driven and shaped by social, economic, political & neocolonial forces. “Until we all understand how social pathologies like racism and gender inequity get in the body and how we get them out, we’ll always struggle with health disparities,” he told me in our interview. In his books, he consistently promoted the need for a multidisciplinary approach to solving healthcare challenges that is biosocial. He inspired a whole generation of physicians to also train in anthropology and other social sciences.

“Paul had a remarkable ability to unveil linkages that are so often concealed by the victors of history,” said Ishaan Desai, currently a medical student at Harvard University. Desai worked as Paul’s research assistant for many years. “In explaining the distribution of infectious diseases, for example, Paul pushed us to reckon with a global hierarchy—rooted in histories of oppression and impoverishment—that shields some of us from harm while imperiling countless others,” Desai said.

“Paul helped make clear why it’s important for clinical medicine and public health to understand and help counteract structural violence,” said Rishi Manchanda, CEO, HealthBegins. “He reminded us that health and human rights is a moral pursuit that requires courage – to demand increased investments in public resources and accountability and to confront the profiteering, privatization, and systems that continue to put people in harm’s way,” he added.

“Do not be afraid to criticize the most powerful actors and agencies in the world,” is a key lesson for Sridhar Venkatapuram, Associate Professor of Global Health & Philosophy at King’s College London. Venkatapuram gave the example of Paul’s advocacy to increase access to HIV medicines. “Paul changed the conversation when he called out of certain US government officials as being racist when they testified before Congress that US should not provide AIDS medicines to Africans because they did not have watches or could not tell time to manage taking medicines,” he explained.

Lesson 7: Engage communities

“Community engagement cannot go wrong and has to be practiced in all corners of the world,” is a key lesson for Shubha Nagesh, Chapter Development Manager, Women in Global Health, India. She also learnt from him about the critical importance of employing people from the communities we serve.

Indeed, PIH, the NGO that Paul co-founded, is well known for their community engagement and advocacy strategy. PIH organizes local communities toward building a global movement for the right to health. They recruit, train, and equip dedicated teams of volunteer community organizers who mobilize their communities in the fight for health equity.

Lesson 8: Irrigate clinical deserts

In his most recent book, “Fevers, Feuds, And Diamonds,” Paul wrote that “most of West Africa is a public health desert, which is why Ebola spreads there, and it is a clinical desert, which is why it kills there.” His book provides compelling data on how an overwhelming majority of the mostly White American and European healthcare workers who contracted Ebola survived (because they got modern care in US or European hospitals), while the infection killed two-thirds of their West African peers. Many died because even simple intravenous rehydration treatment was not made available to them in the clinically barren settings they were in. Paul had a term for deaths that could have been easily prevented or treated. He called them ‘stupid deaths.’

“People, when they are sick, are not looking to be sprayed, controlled, counselled, told about bush meat… they are looking to survive, and when they see the quality of care is not good, they are going to flee… Control without care is what amplified the West African Ebola epidemic,” Paul told me during a 2018 interview.

Paul’s entire life was dedicated to irrigating clinical and public health deserts. In fact, he considered it the “price of admission for all who engage in the noble struggle for global health equity.” Through his work with PIH and others, he demonstrated that it is indeed possible to bring modern medical care to Haiti, Peru, Rwanda, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and many other settings. He showed that it is possible to scale-up the treatment of HIV and drug-resistant tuberculosis. Both treatments were initially seen as ‘not cost-effective.’ “The more desiccated the medical desert, the greater the possibility for rapid change,” he told me in my interview.

“Paul taught us that providing health care to people in need is always a good thing. Building the systems that make it possible (the famous 5s – staff, stuff, space, systems and support) – is always a good thing. But actually living the implications of believing that all people are worth it is so much harder. That’s what Paul challenged us all to do. It’s what he called living in the House of Yes,” said Mark Brender, National Director, Partners In Health Canada.

“In a world riven by inequity, medicine could be viewed as social justice work,” sums up Paul’s approach to medicine.

Lesson 9: Be in it for the long haul

Gene Bukhman, a cardiologist and medical anthropologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, was Paul’s student. “I think the biggest thing I learned from Paul goes back to a very early conversation I had with him. I was sure that all forms of tuberculosis would be virtually wiped out very soon given how focused he was on this issue. It was ridiculous that such a treatable disease should persist in the 21st century! He looked at me incredulously, and said “Oh no, this it the kind of thing that people die working on.” I think I learned that this was the sort of commitment – measured in decades – that it takes to repair the world.”

Indeed, in his books, Paul has written about the need for global health to be ‘more than just a hobby.’

Lesson 10: Counter failures of imagination

We are living in the midst of multiple global threats – Covid-19, climate crisis, and conflicts. None of these global threats can be solved without equity, global solidarity, transnational cooperation, and global citizenship. As Paul wrote, “we live in one world, not three (first, second, third), and “reimagining global health” requires resocializing our understanding of it.”

Think bigger, build bigger, and counter failures of imagination was one of Paul’s most important teachings. “Countering failures of imagination” was the title of his commencement speech at Northwestern University in 2012.

Looking at the dysfunctional and inequitable way the world is dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic and the climate crisis, I cannot but wonder if this may well be Paul’s most important message – that humankind must be bold enough to counter failures of imagination.

Can we imagine a world where everyone has access to Covid-19 vaccines and boosters? Can we imagine a world where countries cooperate to mitigate the climate crisis, where rich polluting nations pay for the climate damage they have caused? To imagine these radical futures, we must counter failures of imagination. The long journey to bending the arc towards justice begins, first and foremost, in our imagination.

Originally published on forbes.com